By Julius Nyangaga

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact our daily lives, most of us the world over now know what it takes to avoid getting sick. We can change our individual behaviors (e.g. wearing masks and avoiding indoor group gatherings) to help minimize the chance of being infected or infecting others.

But in addition to individual behaviors that can increase or decrease risk, there are also group and institutional practices and systems that can affect our risk. These practices and systems aren’t controlled by a single person but by an immeasurable number of stakeholders. That’s where Outcome Mapping comes in.

What is Outcome Mapping?

Outcome Mapping is a participatory process that brings stakeholders together to engage them in the design, monitoring, and evaluation of a project or intervention in order to bring about sustainable social change. The process - which involves a series of facilitated conversations between stakeholders - helps a team to be specific about the actors (or partners) it wants to target, the changes it hopes to see, and the best strategies to achieve these changes.

The approach was initiated by the International Development Research Centre in 2000 to support the organization’s research-to-action programs, with a manual published in 2001. Since then many individuals, organizations and programs have used this process, adapting its concepts and tools in their project designs, management and monitoring systems. The Outcome Mapping Learning Community has a map displaying 86 case applications across the globe (some current, many past). Those shown span a wide range of sectors from human nutrition and health, to environment and climate change, to economic empowerment, to addressing human rights and managing conflicts.

The cases show how Outcome Mapping has been used as a research analytical model, for program monitoring and evaluation, and enabling project teams to address and manage the complexities of context as drivers of behavioural change. The approach is frequently used to enhance the uptake and utilization of program outputs (i.e. interventions), especially policy recommendations. For example, PRISE (Pathways to Resilience in Semi-arid Economies), a program implemented from 2014-2018 by a global R&D consortium led by the Overseas Development Institute, used the approach to generate knowledge that could be used to support communities in arid and semi-arid regions increase their resilience to climate change. They noted that approach provided a “systematic analysis of outcome level changes, feeding that information back to stakeholder engagement strategies and related activities”.

Why Use Outcome Mapping?

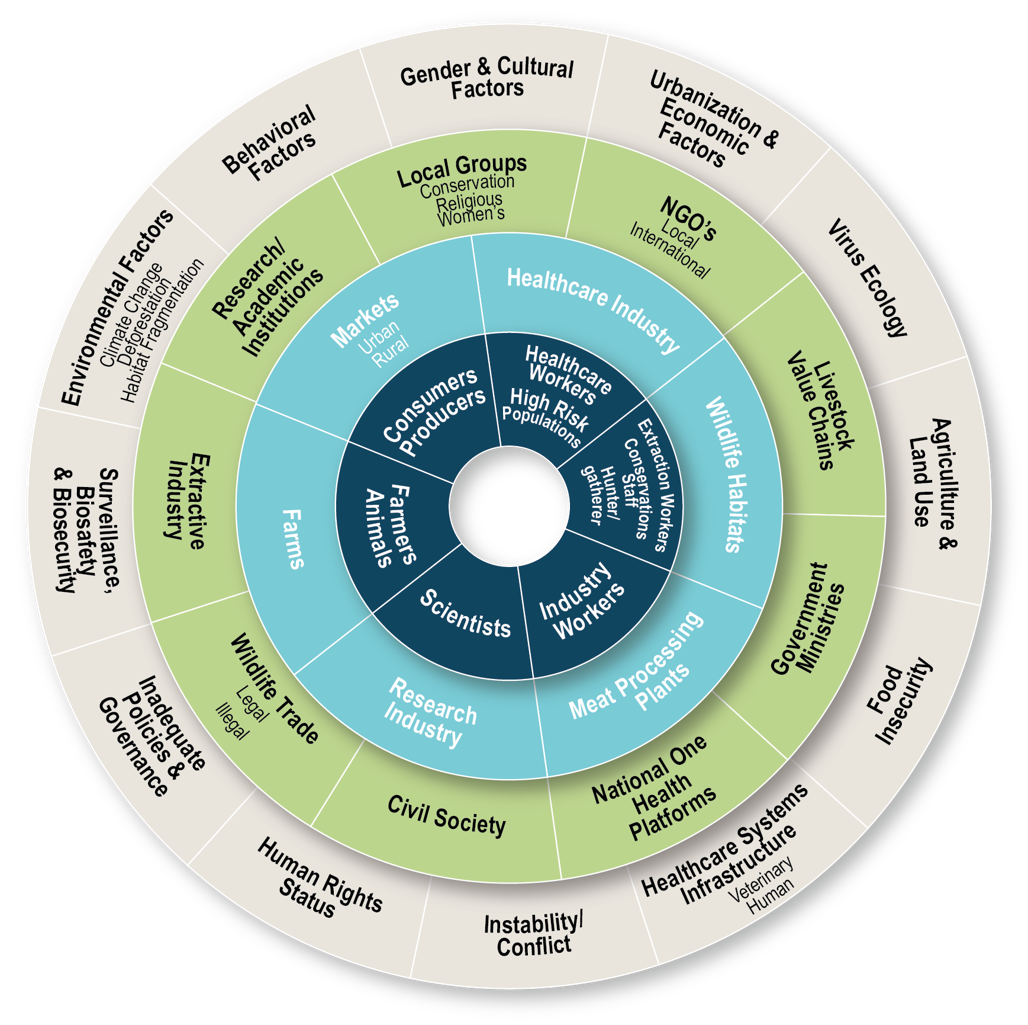

Disease spillover ecosystems consist of a wide range of drivers that influence the risks of viruses spilling over from animals to humans. These factors can range from land access and use to inclusivity and how human rights are respected. They can also include value chain relationships, public policy, and regulation systems. These factors influence a whole slew of behavioural changes critical to managing the current and other potential pandemics. Some of these behaviors are individuals’ own ways of life, while others are those associated with group dynamics, institutional cultures, practices, and systems.

The participatory nature of Outcome Mapping can nurture multi-stakeholder dialogues that are well suited to successfully setting up and managing One Health programs like STOP Spillover.

How STOP Spillover is Using Outcome Mapping

Addressing behaviors that increase spillover risk is the foundation of the STOP Spillover project – a 5-year, multi-country USAID-funded initiative. The success of the project depends largely on how stakeholders’ behavioural transformation influences levels of exposure and degrees of risk.

STOP Spillover is using the Outcome Mapping approach to identify and prioritize potential high-risk spillover interfaces (places where viruses are likely to make the jump from animals to humans), the critical partners around those interfaces, and relevant behavioural-change outcomes that are likely to decrease the risk of spillover. The stakeholders will be involved at every step - from the intentional design processes for each country and interface, to the implementation of appropriate risk-reduction interventions, and the use of informative monitoring systems.

Participants in STOP Spillover’s first Uganda Outcome Mapping session noted:

- The process “has really brought out the advantages of bringing different stakeholders together to combat any issue.”

- “There appears to be a wide range of spillover knowledge and priorities among stakeholders. Finding a way to reconcile these and agree on common priorities is needed.”

- “No single sector can address spillover effects.”

Taking the Outcome Mapping approach will help ensure that STOP Spillover’s priorities are stakeholders’ priorities, and that we’re working closely and effectively with stakeholders at every step to prevent future zoonotic spillovers and pandemics.

To learn more about Outcome Mapping and how STOP Spillover is using the Outcome Mapping approach, read our recent publication, “Spillover Ecosystem Stakeholder Engagement, Gap Analysis, and Intervention Design Using Outcome Mapping”.