By Susan Babirye

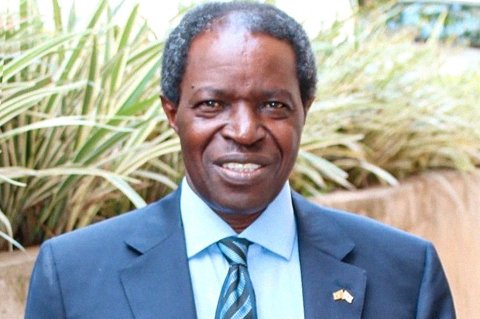

Dr. William Bazeyo is the Chief Executive Officer of the Africa One Health University Network (AFROHUN) and former dean of the School of Public Health, Makerere University. As a physician, public health specialist, and researcher, he is focused on occupational health and strengthening the resilience of communities through innovative educational approaches. This week I sat down with Professor Bazeyo to talk about AFROHUN, his passion for One Health, and his aspirations for STOP Spillover.

Susan: Thank you Professor Bazeyo for giving me time for this interview. I will begin by asking you to tell us about AFROHUN and its mission.

Professor Bazeyo: AFROHUN is new, but also has a long history.

The organization started as the Leadership Initiative for Public Health, which was a project funded by USAID in 2009 and led by two schools of public health - Makerere University in Uganda and Muhimbili University in Tanzania. Its aim was to look at the limitations in public health leadership in the region. At that time, leaders were working in silos - public health people working only on public health and clinicians working only in clinical medicine. So, there was a big gap in public health that needed to be addressed, and we responded to that call.

Halfway through this project the mission was expanded to include looking at and addressing gaps in both veterinary medicine and public health since viruses between humans and animals can mix, and we incorporated the veterinary schools of Makerere University and Muhimbili University. That was the first effort at breaking those silos and having veterinarians work alongside public health professionals in the field and at hospitals.

When that project was winding down, One Health was still a new term, but we knew how important breaking down silos was from our previous work, and so we established One Health Central and Eastern Africa. We improved curricula at schools in eight African nations, developed a database of all the professionals in public health and veterinary medicine at our member universities, and started exchange programs for faculty across institutions and countries so that they could learn from each other. We also brought wildlife stakeholders on board, and established field sites where veterinarians, medics, and public health professionals could get practical training together, make better diagnoses, and interact with the communities they serve. This effort expanded to other countries and other schools and evolved into the Africa One Health University Network - or AFROHUN.

Susan: What do you believe is the one strategy that can best prevent emerging zoonotic diseases?

Professor Bazeyo: The best way to prevent emerging zoonotic diseases is to involve everybody at all levels. We must bring everyone to the table, identify the problem, identify the gap, and agree on the solution and how to manage the gap.

Communities must be connected with veterinarians, public health professionals, and wildlife stakeholders and be made aware of the effects of interacting with animals, or they will continue to mingle with, hunt, eat, and stay with animals in their homes without knowing the possible dangers or consequences. Only together, can we prevent emerging zoonotic diseases.

Susan: AFROHUN recently helped launch STOP Spillover. What is your vision for this project in Africa?

Professor Bazeyo: USAID has made incredible investments in building expertise and infrastructure in One Health across the region, and STOP Spillover has the potential to leverage USAID’s investments and have a major impact. STOP Spillover will build on the previous work of AFROHUN, bringing communities and policy makers together to make collective decisions to address emerging diseases.

I believe the challenges we’ve faced with COVID-19 have awakened the different sectors to know that working together is the only way to manage disease outbreaks. We should now take advantage of this momentum to implement interventions that will reduce risk when people are still eager and anxious to see what happens.

Susan: How is AFROHUN uniquely positioned to implement the STOP Spillover Project?

Professor Bazeyo: AFROHUN is the only one network I know that brings together institutions of higher learning from different countries across Africa and with different viewpoints and makes them equal partners when addressing problems. In addition, AFROHUN champions working with communities and has members from across the continent.

Susan: What do you think are the biggest challenges to preventing spillover

Professor Bazeyo: The biggest challenge is that to date, there has not been a systems approach to preventing spillover incidents. There are systems in place to prevent disease in animals and man, but there has not been a focus on addressing spillover from animals to humans.

Susan: What impact do you think the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the trajectory of addressing future spillovers?

Professor Bazeyo: I think COVID-19 has shown the world that spillover is imminent, it is possible, and it can happen anywhere in the world whatever level of development. We should use the terrible destruction that COVID-19 has caused as a case study of what can happen, and bring more people into the conversation, especially those who were not included before. COVID-19 underscored the need to stop diseases before they spill over.

Susan: You spoke so passionately about One Health, why do you personally care about it as an approach to preventing emerging diseases?

Professor Bazeyo: The health of the animals around us directly impacts our health. Some of the most devastating and difficult diseases come from animals. I believe that if we have well-trained professionals in the One Health space we can better manage disease outbreaks and spillover events, and have better health outcomes. I am proud to have supported Makerere University in allowing veterinary graduates to complete a Masters in Public Health at the school of public health. By the way, some people don’t call me by my name and instead call me “Mr. One Health,” and I am okay with it!

Susan: When you were a child, what did you aspire to be when you grew up and why?

Professor Bazeyo: I always aspired to be a medical doctor because illness was very present in my childhood. Both my mother and I were sick for the majority of my childhood. I was taken to the hospital many times and the doctors and nurses would treat me. I wanted to be able to treat and cure my mother. I also believe medical treatment can bring happiness to those who are suffering. I am very happy I became a medical doctor and offered myself to save lives.

Susan: Do you have a favorite book? What is it and why?

Professor Bazeyo: I have two favorite books. One of them is “Peaks and Valleys”, by Spencer Johnson. It is a small book that you can read in not more than two hours. The second book that I like is “Ask without Fear” by Marc A. Pitman. It shows you that the only way you can be somebody or achieve something is to “ask”. Ask and you will know. Ask and you will be given.

Susan: What advice would you give to leaders around the world who want to prevent the next pandemic before it starts?

Professor Bazeyo: Everyone has value when it comes to preventing epidemics whether it’s a politician, a businessperson, a farmer, medic, or engineer. Let everyone’s views be heard.

To learn more about AFROHUN, visit www.afrohun.org.